Listen to the audio version >>

Notwithstanding its many downsides, the era of neoliberal globalization had one significant claim to success: the growing wealth of once-poor countries, based largely on their ability to export into the global market. The era of polycrisis appears to be reversing that dynamic. The presidency of Donald Trump is likely to further aggravate global inequality and poverty.

The decades of neoliberal globalization allowed a remarkable decrease in economic inequality among countries. While this largely reflected the rise of China, it also resulted from the growing wealth of many other countries in what used to be referred to as the “third world.” The globalization of trade and investment allowed many countries to make gains relative to the established wealthy nations.

However, these national advances did not translate into greater equality or a greater share of wealth for the world’s less wealthy people. Income and wealth inequalities have been on the rise nearly everywhere since the 1980s, following what the World Inequality Report 2022 characterizes as “a series of deregulation and liberalization programs.” The richest 10% of the global population currently takes 52% of global income, whereas the poorest half of the population earns 8.5% of it. The poorest half of the global population barely owns any wealth at all, possessing just 2% of the total. In contrast, the richest 10% of the global population own 76% of all wealth. The gap between the average incomes of the top 10% and the bottom 50% of individuals within countries has almost doubled over the past two decades, from 8.5 times as much for the top to 15 times as much for the top. The collective wealth of billionaires has risen by 120% in the past decade.[1]

According to the World Inequality Report 2022,

Global inequalities seem to be about as great today as they were at the peak of Western imperialism in the early 20th century. Indeed, the share of income presently captured by the poorest half of the world’s people is about half what it was in 1820, before the great divergence between Western countries and their colonies. [2]

Neoliberal globalization made it possible for export-oriented economies to compete for markets and investment, leading to more of a “level playing field” in national competition and some national economic development. As economists Dani Rodrik and Joseph Stieglitz put it, “global value chains” became “the predominant force shaping global production.” Joining global value chains became “the main vehicle for promoting economic growth.”[3] That often led to growing wealth both for global corporations and for local elites.

But two dynamics of the era of globalization contributed to the shift of this growing national wealth from the bottom to the top – a kind of “Robin Hood in reverse.”

First, structural adjustment plans and other “neoliberal” economic policies imposed on less developed countries slashed labor laws, shifted taxes from the rich to the poor, and dismantled public programs for food, housing, education, and other social needs, to the benefit of wealthy private owners. Over the past 40 years, countries have become significantly richer, but their governments have become significantly poorer.

Second, neoliberal globalization has put all countries in competition with each other to see who can provide the cheapest labor and environmental conditions and the largest subsidies. The result has been a “race to the bottom” in labor and environmental conditions. Global corporations play nations and workforces off against each other to see who will provide the most profitable conditions. And local elites advance in global competition by depressing the conditions of their own workers and environment.

This growing inequality stems from the difference in wealth accumulation rates between the rich and the poor. The wealth of the richest individuals on earth has grown at 6 to 9% per year since 1995, whereas average wealth has grown at 3.2% per year. Since 1995, the share of global wealth possessed by billionaires has tripled from 1% to over 3%.

While the working people of the world have been forced to compete with each other just to make a living, nearly half of the additional wealth they have created has been engrossed by approximately 3000 billionaires.[4]

Inequality and Polycrisis

It is too early to have complete statistical evidence of how the transition from neoliberal globalization to polycrisis has affected inequality. We do know that half of the world’s poorest countries are poorer now than they were before the COVID pandemic.[5] And some dynamics are already detectible:

Global financial “system”

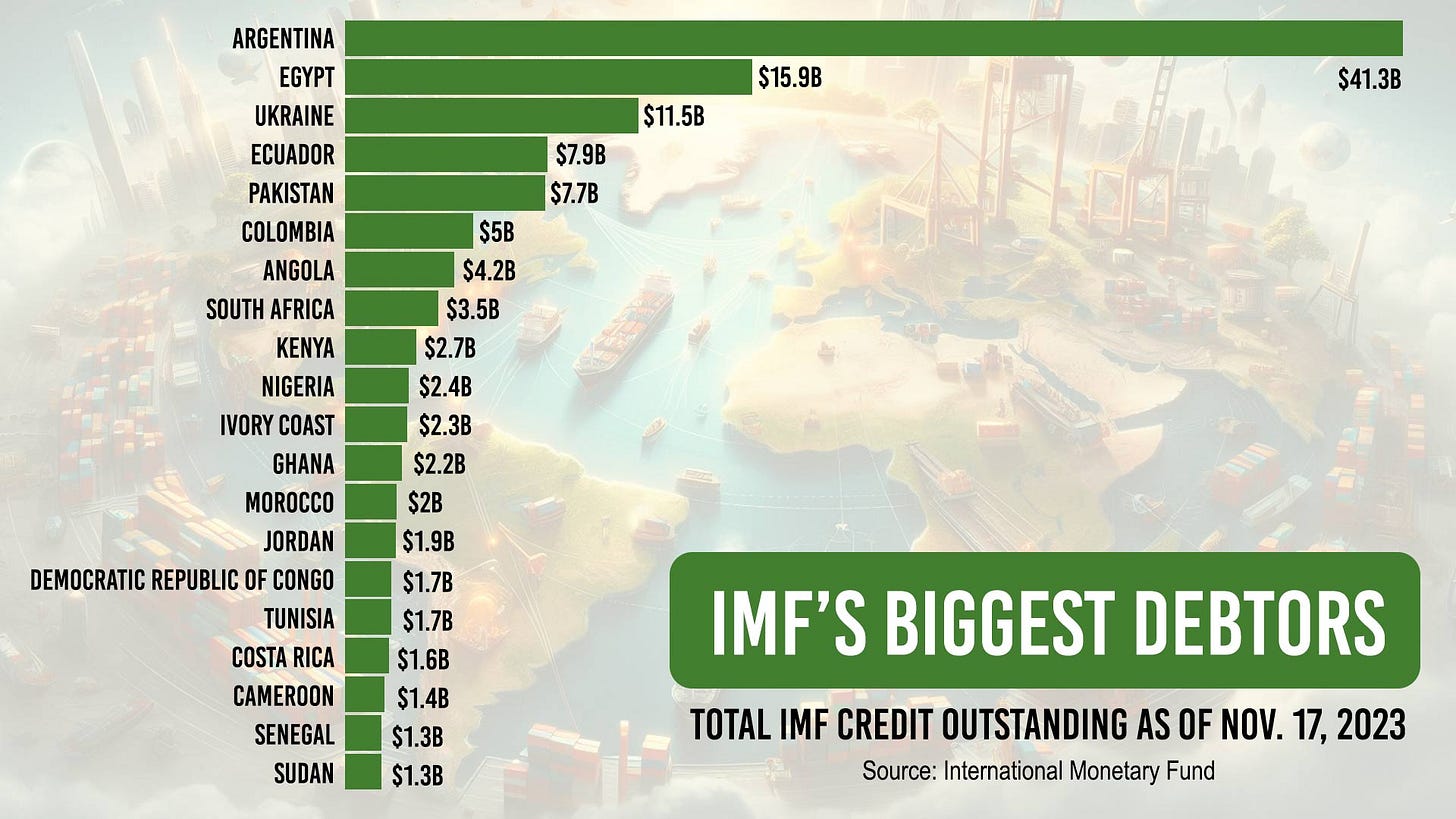

The unregulated global financial system puts poor countries at its mercy. The current phase of the polycrisis is marked by a cascading crisis of debt. According to the World Bank, in the past three years alone there have been 18 sovereign debt defaults in 10 developing countries – greater than the number recorded in all the previous two decades. 60% of low-income countries are at high risk of debt distress or are already in it. Interest payments for 75 low-income countries quadrupled in the past decade. In 2022, private creditors nearly halted lending to developing countries, pulling out $185bn more in principal repayments than they disbursed in loans.[6]

Instability

Lack of global regulation creates greater boom/bust gyrations. These dynamics are already visible in the wave of extreme inflation in 2023, the approximate doubling of Western interest rates in response, and the consequent drain of dollars out of developing countries.

Restricting export-led development

The diversion of trade and investment to countries that the great powers regard as friendly (or that can be coerced into acting that way) makes development contingent on reduction in sovereignty. “Friendshoring” also weakens the ability of poor countries to “bootstrap” by winning export markets through cheaper production. This has been central to the advance of China and other successfully developing countries, even though it has been achieved at the cost of extreme exploitation of labor and environment and a transnational “race to the bottom” in labor and environmental conditions. Friendshoring closes the door on even this ambiguous form of development. Competitiveness measured in economic terms no longer ensures development through economically competitive exports. That leaves the alternatives as submission to the dictates of “friends” or no development at all.

Forget the poor

Fragmentation, nationalism, and my-country-first-ism is leading to a decline of even lip service to alleviating global poverty through such means as the Millennium Goals. Overall decline in global cooperation has rapidly undermined global cooperation for any altruistic action. According to Axel van Trotsenburg, senior managing director of the World Bank,“After decades of progress, the world is experiencing serious setbacks in the fight against global poverty, a result of intersecting challenges that include slow economic growth, the pandemic, high debt, conflict and fragility, and climate shock.”[7]

War

According to the Uppsala conflict data program, the past two years have seen more violent conflict than at any time since the end of World War II. The proliferation of war is directly harming wide swaths of the world, especially poorer countries and people. The allocation of growing amounts of wealth and production to war and preparation for war is diverting resources needed for development and even for survival in poorer parts of the world. Military preparation and war aggravate inequality.

Climate crisis

It is a truism, but nonetheless true, that poorer people and countries contribute the least to climate change but face its most devastating impacts. The top 10% of individuals are responsible for close to 50% of all emissions, while the bottom 50% produce 12% of the total.[8] As the impacts of climate change accumulate and the efforts to address it stagnate, the predictable result will be a disproportionate deterioration of wellbeing for countries and people at the bottom and a consequent increase in inequality – even if the great majority of other people are also adversely affected.

The presidency of Donald Trump is likely to aggravate the polycrisis generally and specifically aggravate global inequality. There is little chance that Trump will support financial aid or debt reduction for the developing world; on the contrary, he is likely to steer financial policy in ways that further bankrupt developing countries. Trump’s “America First” trade policies and other economic nationalism will further restrict the opportunity for developing countries to “bootstrap” through export-led development. Trump is indifferent or hostile to efforts to alleviate global poverty. His pugilistic MAGA nationalism and antagonism to efforts at international cooperation are likely to exacerbate war and conflict around the world. His climate change denialism and his acceleration of fossil fuel extraction and burning will escalate the climate catastrophe. In sum, Trump will aggravate the polycrisis in ways that will further aggravate global poverty and inequality.

[1] Rupert Neate, “Taylor Swift among 141 new billionaires in ‘amazing year for rich people’” The Guardian, April 2, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2024/apr/02/world-gains-141-new-billionaires-in-amazing-year-for-rich-people

[2] Lucas Chancel, Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez & Gabriel Zucman, ed. “The 2022 World Inequality Report,” Harvard University Press, November 1, 2022. The World #InequalityReport 2022 presents the most up-to-date For statistics in inequality see the annual World Inequality Report https://wir2022.wid.world/www-site/uploads/2023/03/D_FINAL_WIL_RIM_RAPPORT_2303.pdf, and the World Inequality Database (WID.world)..

https://wid.world

[3] Dani Rodrik and Joseph E. Stiglitz, “A New Growth Strategy for Developing Nations,”, January 2024. https://drodrik.scholar.harvard.edu/sites/scholar.harvard.edu/files/dani-rodrik/files/a_new_growth_strategy_for_developing_nations.pdf

[4] Cancel et al., “2022 World Inequality Report,” Ibid. . The World #InequalityReport 2022 presents the most up-to-date

[5] Kate Mackensie, Tim Sahay, “New World Order?”, Phenomenal World, April 17, 2024. https://www.phenomenalworld.org/analysis/new-world-order/

[6] Larry Elliott, “World Bank warns record debt levels could put developing countries in crisis,” The Guardian, December 13, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/dec/13/world-bank-debt-levels-countries-crisis

[7] Larry Elliott, “Wars, debt, climate crisis and Covid have halted anti-poverty fight – World Bank,” The Guardian, October 15, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2024/oct/15/wars-debt-climate-crisis-covid-poverty-world-bank

[8] Cancel et all, “2022 World Inequality Report,” Ibid. The World #InequalityReport 2022 presents the most up-to-date/

Thank you, Jeremy. Such a troubling situation. I "do what I can"! I'm a small "consumer" --- and LIKE a "simple life" with less material. Still -- wish there were more ways to live that could help our little planet. Thank you for all you work and sharing information!